How To Learn Gemara Like a Talmud Professor

A Guide for the (Ex) Yeshiva Bochur

Academic Biblical scholarship is a massive, accessible field. With resources like TheTorah.com and introductory books like James Kugel's "How to Read the Bible," anyone can dip their toes into critical study of the Tanakh. It makes sense, as the Bible is a foundational text for billions, and fairly accessible.

Talmud scholarship, however, feels different. It's a much smaller academic pond, and the water can seem murky from the outside. The Talmud itself is notoriously challenging. It requires years of dedicated yeshiva study to navigate its blend of Hebrew and Aramaic, its dense legal arguments, and its unique dialectic style. Even with modern tools like the excellent Sefaria online library offering English translations and linked commentaries, the text remains dauntingly huge and complex. The field of academic Talmudic criticism is a tiny one, the best scholars being those who possess both deep traditional yeshiva training and rigorous academic backgrounds.

This post is for those already comfortable navigating a daf of Gemara in the traditional way, who possess the love of leining up a sugya and figuring out pshat. I will show how academic scholars approach the Talmud, offering a different lens. (If you stumbled upon this, completely new to the Talmud and curious about what it even is, I highly recommend checking out this podcast episode for a great overview.)

So, how does one start learning Gemara like a professor?

The First Step: Source Criticism (Yes, for Gemara!)

You may have encountered source criticism regarding the Bible, the Documentary Hypothesis suggesting the Torah is composed of different source documents (J, E, P, D, R). Depending on your background, you might see this as established fact or pure kefirah.

But when we talk about source criticism in the Talmud, it’s far less speculative and, honestly, pretty obvious once it’s pointed out. The Gemara isn't a monolithic text dictated by a single voice. It’s a layered composition. The fundamental first step in academic Talmud study is learning to identify and disentangle these layers or "strands."

Think of it like archaeological strata. Different periods left different deposits. Recognizing these is key. In the Bavli, we generally identify four main strands:

What Are the Four Strands?

Tannaitic Sources: These are texts by the Tannaim, the rabbis of the Mishnah era (roughly 1st-2nd centuries CE). They are always in Hebrew.

Mishnah: The core Tannaitic legal code compiled by Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi. It forms the bedrock upon which the Gemara builds.

Beraita: A Tannaitic teaching similar in style and authority to a Mishnah, but not included in Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi's final compilation. Beraitot are often introduced in the Gemara with phrases like "Tanya" (תניא - It was taught) or "Tanu Rabbanan" (תנו רבנן - Our Rabbis taught).

Amoraic Sources (Memrot): These are statements attributed to the Amoraim, the rabbis who lived after the Mishnah was sealed (roughly 3rd-5th centuries CE in Babylonia). These are usually in Hebrew (though sometimes in Aramaic, especially if aggadic) and are typically concise legal rulings, interpretations, or aggadic statements. They are often introduced by "Amar" (אמר - He said), followed by the Rabbi's name.

Biblical Sources: These are direct quotations from the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible). They are introduced by formulaic phrases like "Dichtiv" (דכתיב - As it is written) or "Ketiv" (כתיב - It is written). Naturally, these are in Biblical Hebrew.

The Stam (סתם - Anonymous/Unattributed): This is arguably the most fascinating and crucial layer for academic study. The Stam is the anonymous Aramaic narrative voice that forms the connective tissue of the sugya. It's what yeshiva learners often colloquially call "the Gemara says." The Stam functions like a skilled editor and narrator:

It quotes the Beraitot, Memrot, and Biblical verses.

It asks questions (e.g., "Mai Ta'ama?" - מאי טעמא - What's the reason?).

It raises contradictions ("U'reminhu" - ורמינהו - And they raise a contradiction between sources).

It proposes answers and reconciliations ("Ela Lav..." - אלא לאו - But is it not..).

It analyzes and interprets the earlier sources, guiding the reader through the logical flow of the argument.

Think of the Stam as the layer most analogous to Rashi and Tosafot – commentators who analyze and explain the base text – but this commentary layer was integrated into the text before its final canonization.

So, Who is the Voice Behind the Stam?

This is a major question in academic Talmud. Was the Stam the work of one or two brilliant final editors, like the traditionally cited Rav Ashi and Ravina? Or perhaps it's the accumulated discussions of several generations of later rabbis (dubbed the Stammaim by Halivni) who lived after the Amoraim but before the Geonic period? Or perhaps it’s simply the editorial activity from the early Geonic yeshivas, recording and standardizing the arguments?

There's no definitive consensus. Different scholars give different theories. Regardless, recognizing the Stam's voice, as distinct from the earlier Tannaitic and Amoraic sources it quotes, is fundamental to the academic approach.

How to Read Like a Professor: Disentangling the Layers

Knowing these strands exists is one thing, but using that knowledge is where the fun begins. Here’s how you do it:

Isolate the Sources: When reading a sugya, actively identify each component: "This is the Mishnah." "This is a Beraita." "Here's a Memra from Rabbi Yochanan." "Here's a quote from Psalms." "And this part – the questions, the transitions, the analysis – is the Stam's Aramaic framework."

Initial Independent Reading: Before considering the Stam's interpretation, try to understand each source (Mishnah, Beraita, Memra) on its own terms. What might this Tannaitic ruling have meant in its original 2nd-century context? What seems to be the plain meaning (pshat) of this Amoraic statement?

Analyze the Stam's Project: Now, look at what the Stam does with these sources. How does it interpret the Mishnah? Does it read the Memra in a way that seems obvious, or does it introduce a subtle twist? How does it try to reconcile apparent contradictions?

The key insight here is that the Stam has an agenda, often driven by specific interpretive principles. For instance, the Stam generally assumes:

Amoraim do not fundamentally argue with Tannaim on matters of law decided in the Mishnah.

Contradictory Tannaitic or Amoraic sources must somehow be harmonized or assigned different contexts.

The entire body of rabbinic teaching forms a coherent, unified system.

An academic scholar, however, does not necessarily share these assumptions. They might look at a sugya and conclude:

"This Beraita directly contradicts the Mishnah. The Stam performs complex logical gymnastics (a chiluk, a change in circumstance) to make them fit, but perhaps they simply reflect differing early traditions."

"The Stam interprets Rabbi X's statement in light of Rabbi Y's later statement, but read in isolation, Rabbi X might have meant something quite different."

Example: Consider the discussions around a non-Jew studying Torah in Sanhedrin 59a. The Stam navigates seemingly contradictory statements from Rav Yochanan, who says that a non Jew who studies Torah is liable for the death penalty, and Rav Meir who says that a non Jew that studies Torah is like a Kohen Gadol. The stam reconciles the two by saying that Rav Meir is referring to a non Jew who studies the seven Noahide commandments, while Rav Yochanan’s statement is referring to the rest of the Torah. An academic approach might isolate each statement, note the apparent conflicts, and then analyze the Stam's contribution as a sophisticated, but essentially post-facto, harmonization effort. The academic would suggest that the original sources did conflict, reflecting unresolved debates, and the Stam's role was to create a coherent legal narrative out of them, reinterpreting Rav Meir's statements to fit its model.

Just as one might respectfully disagree with Rashi's interpretation of a Pasuk or a line of Gemara, an academic might respectfully disagree with the Stam's interpretation of a Mishnah or a Memra, suggesting alternative original meanings.

Broadening the Horizon: Parallel Texts (Yerushalmi, Tosefta, Midrash Halakha)

Academic Talmudists don't limit themselves to the Bavli text in isolation. They actively seek out parallel versions and related literature:

The Yerushalmi (Jerusalem Talmud): While yeshiva learning often focuses exclusively on the Bavli, the Yerushalmi is a crucial resource for academics. It often discusses the same Mishnayot and sometimes quotes the same Amoraim as the Bavli, but frequently offers vastly different interpretations, arguments, and even textual versions of Tannaitic sources. Comparing a sugya in the Bavli to its counterpart in the Yerushalmi can reveal different interpretive traditions and pathways. Reading the Yerushalmi is a challenge. It's more concise, the language is different, and critically, it lacks the extensive Stam layer of the Bavli, leaving the flow much more open-ended. (If you venture into it, having a good commentary is essential. Rav Chaim Kanievsky's commentary is helpful for navigating the text, though that's probably not what the academics use).

Tosefta and Midrash Halakha: Beraitot quoted in the Gemara often originate in collections like the Tosefta (a parallel compilation to the Mishnah) or the Midreshei Halakha (Sifra, Sifrei, Mekhilta - Tannaitic commentaries on the Torah). Academics will hunt down the "original" context of a Beraita in these works. Frequently, the version or wording found there differs slightly, or sometimes significantly, from how the Bavli's Stam quotes and interprets it. The Stam might quote selectively, or its interpretation might only work with its specific version, not the one found in the Tosefta.

Example: Take the famous stories about Rabbi Akiva. Bavli Berachot 61b gives a dramatic account of his martyrdom while reciting the Shema. However, parallel versions exist in the Yerushalmi (Berachot 9:5 14b, Sotah 5:7 20c) and in the Bavli in Menachot 29. Another story, Rabbi Akiva laughing at a fox running out of the ruins of the temple, appears in both b. Makkot 24a-b and Sifre Deuteronomy 43. Academics compare these versions, noting differences in details, emphasis, and narrative structure. They might trace how the stories likely evolved over time, becoming more elaborate in the Bavli, perhaps reflecting later theological concerns or narrative embellishments. This "diachronic" approach (studying change over time) uses parallel texts to understand the overall development of the sugya.

Digging Deeper: Manuscript Evidence

One last crucial tool is the study of manuscripts. The Gemara we learn today is almost universally based on the Vilna Shas edition, printed in the late 19th century. While a monumental achievement, it's based on relatively late manuscripts and includes editorial choices and corrections. Sometimes, difficulties in understanding a sugya, or entire lines of interpretation built on a specific word, might stem from textual variations or even errors that crept in over centuries of transmission.

Early manuscripts of the Talmud, some dating back centuries earlier than the printing press, often contain different readings (girsaot). A word might be spelled differently, be missing entirely, or a different word might appear altogether. These variations can sometimes resolve textual difficulties or suggest radically different interpretations.

Thankfully, you don't need to be Indiana Jones hunting scrolls in the archives. The Hachi Garsinan database of the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society (FJMS) allows anyone to view digital images of a myriad of Talmud manuscripts and compare readings for nearly any sugya in Shas side-by-side. Seeing how a phrase appears in the Munich, Vatican, or Florence manuscripts, or even in an old Cairo Geniza handwritten fragment, is not only fun but can help explain a sugya better.

Wrapping It All Together

Learning Gemara academically is a vibrant method of learning and more dedicated to getting at the truth behind the sugya than yeshivish pilpul or the brisker method. By learning to distinguish the voices within the sugya - the Tannaim, the Amoraim, the biblical verses, and the anonymous Stam - the Gemara transforms from a complicated back and forth that's difficult to understand into a dynamic, multi-layered conversation unfolding over centuries.

Recognizing the Stam's harmonizing project allows you to appreciate its genius while also retaining the critical freedom to ask: What might these sources have meant before they were woven together? How did interpretations evolve? What do parallel texts and earlier manuscript versions tell us?

Using this approach, you'll have a new way of swimming in the Sea of Talmud. Give it a try, check out some academic Talmudists writings, and you might find yourself falling in love with Gemara all over again.

Very clear.

I do want to point out that this approach (titled revadim or layers by Weiis-Halivni), although a central part of Talmudic analysis, is not the only kind of academic Talmud scholarship. Another major subfield, sometimes under the umbrella term of Rabbinics, is the historical critical analysis of the text, which focuses on comparing rabbinic traditions and methodologies with broader Jewish (such as Hellenistic Jewish, sectarian, or even early Christian) or even non-Jewish (such as Greco-Roman or sassanian) sources, and probably most of the scholarly literature on the Talmud falls into this field (possibly because it's of broader interest towards understanding Judaism holistically).

Good, balanced overview.

Some notes:

1)

"With resources like TheTorah.com" -

the same website also has a sister site for academic talmud, though with far fewer articles.

2)

"The Talmud itself is notoriously challenging. It requires years of dedicated yeshiva study to navigate its blend of Hebrew and Aramaic, its dense legal arguments, and its unique dialectic style. Even with modern tools like the excellent Sefaria online library offering English translations and linked commentaries, the text remains dauntingly huge and complex" -

This assertion is often made, but it's significantly overrated, in my opinion. First of all, there's aggadah, which is at least a quarter of the Talmud, and is relatively straightforward to read and understand. Second of all, even for halachic sugyas, a major thing that makes it difficult is the hairsplitting of the Stam. Much of a sugya is simple statements (as you discuss) and relatively straightforward derivations/reasons (meaning, it's relatively simple to understand the derivation/ explanation being posited).

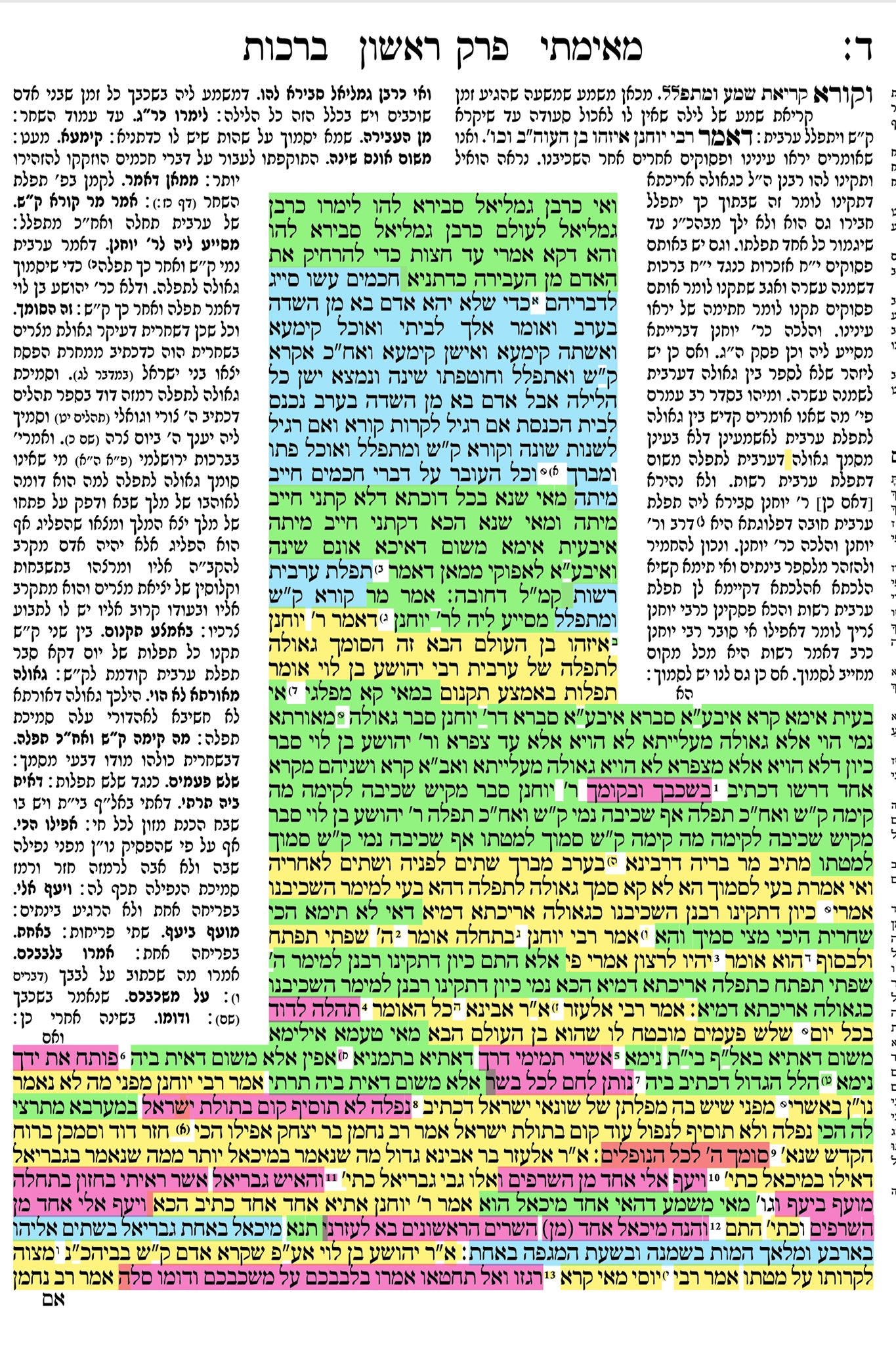

As an aside, one of the things that makes traditional study so (unnecessarily) difficult is the almost complete lack of formatting and standard punctuation in the traditional tzurat hadaf.

3)

re the academic method, your piece focuses on:

- source criticism (רבדים)

- textual criticism (שינויי נוסח, גירסאות)

- parallels in Yerushalmi and other works of חז"ל

Other commenters point to historical/ comparative elements.

I'd like to point out that there are many other elements to the academic method:

- linguistics is fundamental (especially semantic analysis - the precise meanings of terms, and how words and concepts evolve over time)

- understanding how the talmudic rabbis understood the Bible (hermeneutics)

- analysis of literary structure/ rhetoric

- many more